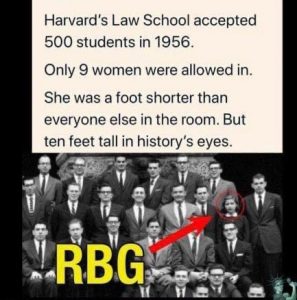

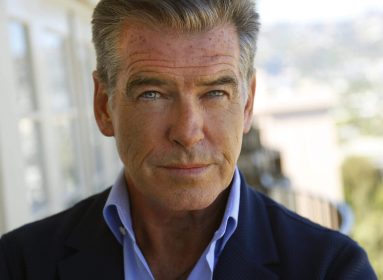

Στην μνήμη της Ανωτάτου Δικαστικού Ruth Bader Ginsberg που απεβίωσε στις 18 Σεπτεμβρίου, 2020.

Ως δικαστής ήταν υπέρμαχος των δικαιωμάτων των γυναικών, των μειονοτήτων και όλων όσων τύγχαναν φυλετικών, σεξουαλικών ή άλλων ειδών διακρίσεων.

Ήταν ένα προοδευτικό, φωτεινό μυαλό σε μια Αμερική όπου ιδιαίτερα τα τελευταία χρόνια ψάχνεται στο σκοτάδι.

& PANE DI CAPO ΣΤΙΣ ΠΗΓΕΣ ΚΑΛΛΙΘΕΑΣ- ΑΡΧΟΝΤΙΚΗ ΑΠΟΛΑΥΣΗ

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

- BORN

- Mar 15, 1933

- Brooklyn, NY

- DIED

- Sep 18, 2020

- ETHNICITY

- German

- RELIGION

- Jewish

- MOTHER

- Celia Amster

- FATHER

- Nathan Bader

- FATHER’S OCCUPATION

- Merchant

ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

- APPOINTED BY

- Bill Clinton

- COMMISSIONED

- Aug 5, 1993

- SWORN IN

- Aug 10, 1993

- SEAT

- 7

- PRECEDED BY

- Byron R. White

Ruth Bader Ginsburg spent a lifetime flourishing in the face of adversity before being appointed a Supreme Court justice, where she successfully fought against gender discrimination and unified the liberal block of the court. She was born Joan Ruth Bader on March 15, 1933 in Brooklyn, New York. Her father was a furrier in the height of the Great Depression, and her mother worked in a garment factory. Ginsburg’s mother instilled a love of education in Ginsburg through her dedication to her brother; foregoing her own education to finance her brother’s college expenses. Her mother heavily influenced her early life and watched Ginsburg excel at James Madison High School, but was diagnosed with cancer and died the day before Ginsburg’s high school graduation. Ginsburg’s success in academia continued throughout her years at Cornell University, where she graduated at the top of her class in 1954. That same year, Ruth Bader became Ruth Bader Ginsburg after marrying her husband Martin, who was a first-year law student at Cornell when they met. After graduation, she put her education on hold to start a family. She had her first child in 1955, shortly after her husband was drafted for two years of military service. Upon her husband’s return from his service, Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law.

Ginsburg’s personal struggles neither decreased in intensity nor deterred her in any way from reaching and exceeding her academic goals, even when her husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1956, during her first year of law school. Ginsburg took on the challenge of keeping her sick husband up-to-date with his studies while maintaining her own position at the top of the class. At Harvard, Ginsburg tackled the challenges of motherhood and of a male-dominated school where she was one of nine females in a 500-person class. She faced gender-based discrimination from even the highest authorities there, who chastised her for taking a man’s spot at Harvard Law. She served as the first female member of the Harvard Law Review. Her husband recovered from cancer, graduated from Harvard, and moved to New York City to accept a position at a law firm there. Ruth Bader Ginsburg had one more year of law school left, so she transferred to Columbia Law School and served on their law review as well. She graduated first in her class at Columbia Law in 1959.

Even her exceptional academic record was not enough to shield her from the gender-based discrimination women faced in the workplace in the 1960s. She had difficulties finding a job until a favorite Columbia professor explicitly refused to recommend any other graduates before U.S. District Judge Edmund L. Palmieri hired Ginsburg as a clerk. Ginsburg clerked under Judge Palmieri for two years. After this, she was offered some jobs at law firms, but always at a much lower salary than her male counterparts. She instead took some time to pursue her other legal passion, civil procedure, choosing to join the Columbia Project on International Civil Procedure. This project fully immersed her in Swedish culture, where she lived abroad to do research for her book on Swedish Civil Procedure practices. Upon her return to the States, she accepted a job as a professor at Rutgers University Law School in 1963, a position she held until accepting an offer to teach at Columbia in 1972. There, she became the first female professor at Columbia to earn tenure. Ginsburg also directed the influential Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union during the 1970s. In this position, she led the fight against gender discrimination and successfully argued six landmark cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Ginsburg took a broad look at gender discrimination, fighting not just for the women left behind, but for the men who were discriminated against as well. Ginsburg experienced her share of gender discrimination, even going so far as to hide her pregnancy from her Rutgers colleagues. Ginsburg accepted Jimmy Carter’s appointment to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 1980. She served on the court for thirteen years until 1993, when Bill Clinton appointed her to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her career as a justice where she left off as an advocate, fighting for women’s rights. In 1996, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in United States v. Virginia, holding that qualified women could not be denied admission to Virginia Military Institute. Her style in advocating from the bench matches her style from her time at the ACLU: slow but steady, and calculated. Instead of creating sweeping limitations on gender discrimination, she attacked specific areas of discrimination and violations of women’s rights one at a time, so as to send a message to the legislatures on what they can and cannot do. Her attitude is that major social change should not come from the courts, but from Congress and other legislatures. This method allows for social change to remain in Congress’ power while also receiving guidance from the court. Ginsburg does not shy away from giving pointed guidance when she feels the need. She dissented in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. where the plaintiff, a female worker being paid significantly less than males with her same qualifications, sued under Title VII but was denied relief under a statute of limitations issue. The facts of this case mixed her passion of federal procedure and gender discrimination. She broke with tradition and wrote a highly colloquial version of her dissent to read from the bench. She also called for Congress to undo this improper interpretation of the law in her dissent, and then worked with President Obama to pass the very first piece of legislation he signed, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, a copy of which hangs proudly in her office.

Until her death on September 18, 2020, Ginsburg worked with a personal trainer in the Supreme Court’s exercise room, and for many years could lift more than both Justices Breyer and Kagan. Until the 2018 term, Ginsburg had not missed a day of oral arguments, not even when she was undergoing chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer, after surgery for colon cancer, or the day after her husband passed away in 2010. Justice Ginsburg proved time and again that she was a force to be reckoned with, and those who doubted her capacity to effectively complete her judicial duties needed only to look at her record in oral arguments, where she was, until her death, among the most avid questioners on the bench. The Supreme Court issued a press release on September 19, 2020, regarding her death.

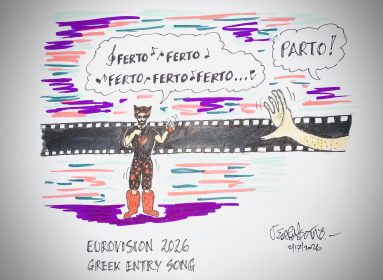

Το σκίτσο είναι του Βαγγέλη Παυλίδη

Το σκίτσο είναι του Βαγγέλη Παυλίδη

Στηρίξτε-Ενισχύστε την iΠόρτα με τη δική σας χορηγία…

Στηρίξτε-Ενισχύστε την iΠόρτα με τη δική σας χορηγία…