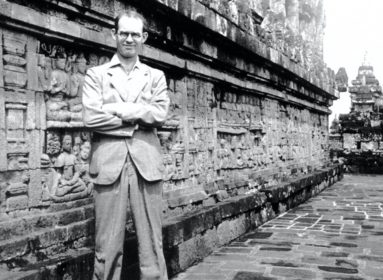

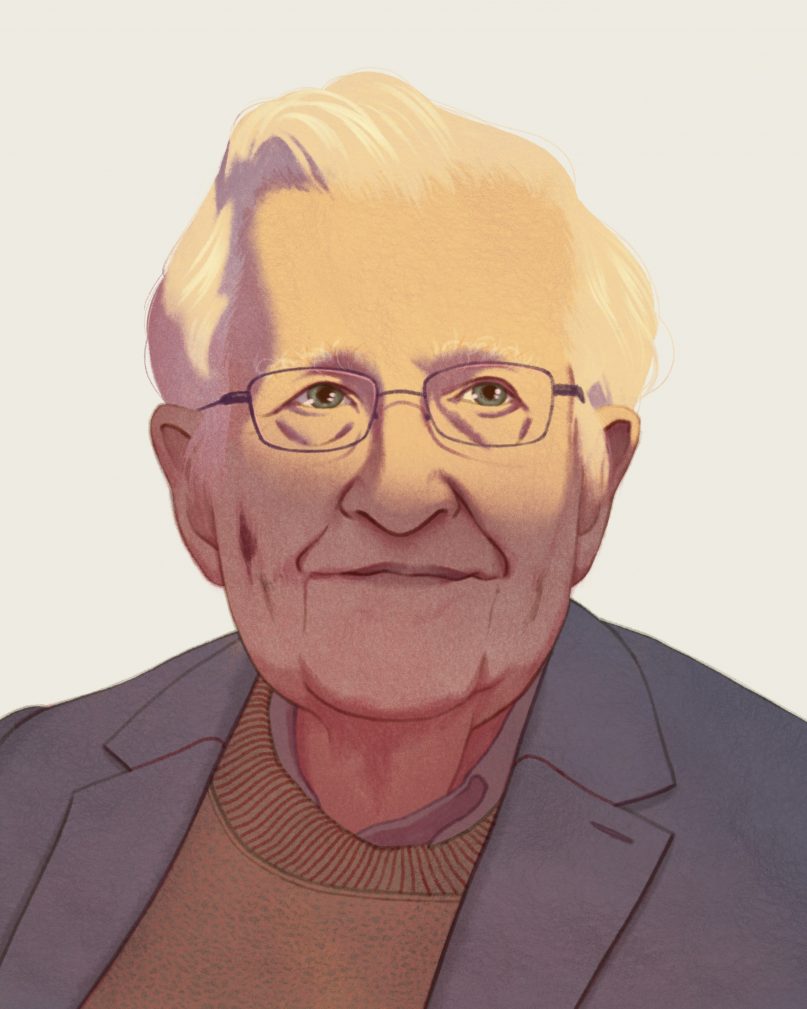

Noam Chomsky, the American linguist, activist, and political writer, is one of the most famous and harshest critics of American foreign policy. His critiques of Presidential Administrations from Nixon to Obama, and the stridency of his views—comparing 9/11 to Bill Clinton’s bombing of a factory in Khartoum, for example—have made him the target of much ire, as well as a hero of the global left. “Chomsky always refuses to talk about motives in politics,” Larissa MacFarquhar wrote in her Profile of him for The New Yorker, in 2003. “Like many theorists of universal humanness, he often seems baffled, even repelled, by the thought of actual people and their psychologies.”

When I called Chomsky, who is ninety-one, last month for a long-scheduled interview, I had meant to discuss his career and life, and his latest book, “Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal,” written with Robert Pollin and C. J. Polychroniou—but he spent most of the hour-long session railing against the Trump Administration with a vehemence that slightly surprised me. Chomsky has always been extremely pragmatic in his political analysis, diverging from some other leftists in his belief in the necessity of voting for mainstream Democrats against Republicans. But in addition to supporting Joe Biden this year, he told me that Donald Trump is “the worst criminal in human history” and expressed serious concerns about the future of American democracy (although he conceded that it “was never much to write home about”). With perhaps not equal concern, but with the same passion he seems to bring to every topic, he also railed against “cancel culture” and explained why he signed the recent Harper’s letter on free expression. And yet, Chomsky noted that what he most loves to think about are philosophy, science, and language. “To tell you the truth,” he said, “while I’m giving interviews and talking about things, one part of my mind is working on technical problems, which are much more interesting.” Our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, is below.

Over the past four years, have we been in a strange and new period of American history? Or are we seeing a continuation of American history that is pretty much in line with what it has always been?

Of course, it’s the same country. We haven’t undergone a major revolution, but the last four years are very much out of line with the history of Western democracies altogether. By now, it’s becoming almost outlandish. In the three hundred and fifty years of parliamentary democracy, there’s been nothing like what we’re seeing now in Washington. I don’t have to tell you. You read the same newspapers I do. A President who has said if he doesn’t like the outcome of an election, he’ll simply not leave office, and is taken seriously enough that, for example, two high-level, highly respected, retired military officers—one of them very well known, Lieutenant Colonel John Nagl—actually went to the extent of writing an open letter to General [Mark] Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reminding him of his constitutional duties to send in the American military to remove the President from office if he refuses to leave.

There’s a long article, which you’ve probably seen, by Barton Gellman, reviewing the strategies that Republican leadership is thinking of to try and undermine the election. There has been plenty of tampering before. We’re not unfamiliar with that. In fact, one case that comes to mind is kind of relevant at the moment: 1960. Richard Nixon had pretty good reason to believe that he had won the election. Nixon, who was not the most delightful person in the history of Presidential politics, decided to put the welfare of the country over his personal ambition. That’s not what we’re seeing now, and that’s only one sign of a very significant change. The executive has been almost totally purged of any critical independent voices—nothing left but sycophants. If they’re not sufficiently loyal to the master, fire them and get someone else. A striking example recently was the firing of the inspectors general when they started looking into the incredible swamp Trump created in Washington. This kind of thing goes on and on.

How do you view the Trump Administration, in terms of America’s role in the world and whether it is new or not?

Well, there are some new things which are not being much discussed. I don’t know if it’s Trump, but the people around him are essentially creating an international alliance of extremely reactionary states, which can be controlled by the White House, which, of course, has shifted way far to the right, tearing up every international agreement, wrecking everything in sight. In the Western Hemisphere, a leading figure would be [Jair] Bolsonaro, in Brazil, kind of a Trump clone, and the Middle East, with Gulf dictatorships, the most reactionary states in the world, and Egypt under [Abdel Fattah El-]Sisi, probably the worst dictatorship in Egypt’s history. Israel has moved very far to the right. The current so-called peace agreements have nothing to do with peace agreements. It’s a very natural Middle East base for the Trump-run reactionary international. In the East, [Narendra] Modi’s India is a prime candidate. He’s smashing Indian secular democracy, trying to impose Hindu nationalist theocracy, crushing Kashmir. They’re an obvious part of it. In Europe, the prime candidate is [Viktor] Orbán’s Hungary. Matteo Salvini’s not yet in power, but Italy’s right behind. There are other pleasant figures around the world, but that’s basically the core of it.

Now, that’s one side of throwing out all international agreements and throwing out any concern whatsoever for the attitudes and priorities of others. It was revealed with typical Trump Administration arrogance in [Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo’s announcement that the United Nations’ sanctions are reinstituted against Iran. Why? Because he says so. The United States brought it to the Security Council and could get virtually no support. So therefore we reinstitute the United Nations’ sanctions unilaterally. That’s the Godfather talking. It doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks. The same is true of every international agreement. The arms-control regime has been torn to shreds, with great danger to us as well as everyone else.

You mention a bunch of dictators that the United States has cozied up to—and not respecting arms-control treaties—but those are things you’ve written about in the past. I’m interested that you say that you think the Trump Administration is a break with the past. How do you think it’s different in some way?

Well, having an arms-control regime is different than not having one. That’s a break, and it’s a break on one of the two most significant issues in human history. We’ve been living for seventy-five years under the shadow of possible nuclear destruction. The arms-control regime that’s been slowly built up over the years—Eisenhower’s Open Skies proposal, the Reagan-Gorbachev I.N.F. treaty, and other pieces—has mitigated the dangers. Trump has been tearing every piece of it to shreds. The only thing that’s left is New start. It has to be ratified by next February. If Trump wins the election or refuses to leave office, it will be gone by February.

The other major threat to human survival in any recognizable form is environmental catastrophe, and, there, Trump is alone in the world. Most countries are doing at least something about it—not as much as they should be, but some of them rather significant, some less so. The United States has pulled out of the Paris Agreement; is refusing to do any of the actions that might help poorer countries deal with the problem; is racing toward maximizing the use of fossil fuels; and, at the same time, just opened the last major nature reserve in the United States for drilling. He has to make sure that we maximize the use of fossil fuels, race to the precipice as quickly as possible, and eliminate the regulations, which not only limit the dangerous effects but also protect Americans.

Step by step, eliminate everything that might protect Americans or that will preserve the possibility of overcoming the very serious threat of environmental catastrophe. There is nothing like this in history. It’s not breaking with the American tradition. Can you think of anyone in human history who has dedicated his efforts to undermining the prospects for survival of organized human life on earth? In fact, some of the productions of the Trump Administration are just mind-boggling.

To answer your last question, even if it was rhetorical, it seems like the Republican Party leading up to Trump had very similar views on climate-change science, even if he’s taken it in a more nihilistic direction.

What leading figure in human history has dedicated policy toward maximizing the use of fossil fuels and cutting down on regulations that mitigate the disaster? Name one.

Bolsonaro perhaps, but yes, I get your—

Bolsonaro, a Trump clone, and that’s following Trump’s lead. Yes, he’s doing it dangerously, but even he hasn’t gone as far as Trump.

You’ve written a lot of books about American foreign policy, and one of the themes is that American foreign policy is often driven by the economic interests of élites. I think that there is a way in which that is still true, and obviously Trump is of the economic élite. But, with Trump, it seems like perhaps his personal desire for money is driving American foreign policy now. I wonder if that’s made you think differently about how American foreign policy is carried out.

Not at all. In this respect, he’s a continuation, but you have to make distinctions. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the best President we’ve had, in my opinion, and was committed to maximizing American power, and the role of [American] economic interest in the world, and so on. Adolf Hitler, in the same years, was committed to that in Nazi Germany, but that doesn’t lead us to conclude that they’re the same thing.

I thought that’s what I was saying, a little bit. Trump seems to care about his own interests and his own survival, and you have talked about American foreign policy previously being driven by the interests of a whole ruling economic élite. I guess maybe that’s a distinction without a difference, because it’s economic élites who are supporting Trump and allowing him to do this, in some sense.

Not only are they supporting him, but he’s serving them slavishly. It’s hard to find an American President who has been more dedicated to enriching and empowering the ultra-rich and the corporate sector—which is, of course, why they’re happy to tolerate his antics. For example, the one real legislative achievement is the tax scam, which was just a giveaway to the very rich and the corporate sector. In fact, everything I’ve just mentioned is the same. When you reduce regulations, you’re putting more money in the pockets of the rich and harming the working class and the poor and everyone else. That’s extreme. When you refuse to fill the National Labor Relations Board with members so that employers can get away with anything they want, you’re serving the rich. We can go right down the list. He’s a very loyal servant of private power, private wealth, and the corporate sector—which is why they let him get away with the kind of antics you see.

It’s kind of striking when you see the great and powerful get together. Take a look at the last Davos conference, in January. There were three keynote speakers. The first, of course, was Trump. They don’t like him. They don’t like him at all because they like to put forward an image of humanism, civilized behavior, decency, “put your trust in us,” that sort of thing. But when he spoke, they gave him rousing applause. They couldn’t stand anything he was saying. There’s this braggart up there ranting about how wonderful he is. They were probably cringing in their seats, but they gave him rousing applause because there’s one line that he said that they understand, which is meaningful: I’m going to put plenty of money in your pockets, so therefore you better tolerate me. That’s the way he’s regarded by the powerful élites here. Yeah, we can’t stand him, he’s a disgusting creature, but he knows which side the bread is buttered: ours.

What you’re saying seems more similar to the mainstream center-left discourse on Trump and the unique threat he poses to American democracy than it does to some left-wing discourse on the same. I’m curious if you’ve been aware of that in your own analysis and if you think that that’s interesting or funny.

Well, I haven’t noticed that. For example, we just went through two of the quadrennial extravaganzas, the Conventions. Lots of coverage of them. Did you hear a phrase about the threat of nuclear war? I didn’t. Maybe somewhere. That’s the one major threat that the world faces. It’s not discussed. You heard some comments about maybe Trump isn’t doing nice things on the climate. Did you hear anything about his being the worst criminal in human history?

The worst criminal in human history? That does say something.

It does. Is it true?

Well, you have Hitler; you have Stalin; you have Mao.

Stalin was a monster. Was he trying to destroy organized human life on earth?

Well, he was trying to destroy a lot of human lives.

Yes, he was trying to destroy lots of lives but not organized human life on earth, nor was Adolf Hitler. He was an utter monster but not dedicating his efforts perfectly consciously to destroying the prospect for human life on earth.

Let’s take some of their publications. A couple of years ago, you may recall the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published a several-hundred-page analysis. They concluded that, on our present course, we’re likely to reach four degrees Celsius, seven degrees Fahrenheit, above preindustrial levels by the end of the century. That’s an utter cataclysm. Any climate scientist will tell you that. And they drew a conclusion from it. We should not put restrictions on automotive and truck emissions. We should limit the restrictions. Can you find a counterpart to that in human history? Please tell me.

I—

Well, I can think of one thing that maybe comes close. The Wannsee declaration, in 1942, where the Nazi party put the finishing touches on the plans to wipe out all the Jews and kill tens of millions of Slavs. Pretty horrifying. Is it as bad as that publication I just mentioned?

I don’t disagree about Trump’s badness. I’m not sure if he’s intending to destroy the planet so much as he’s intending to watch Fox News and is just following terrible policies out of some combination of laziness and nihilism, and being surrounded by crooks and nihilists.

I’m not talking about Trump the human being. I couldn’t care less about him. I’m talking about the policies. The policies are clear; the understanding is clear. There is nobody that’s not living under a rock that can’t comprehend that maximizing the use of fossil fuels and eliminating the restrictions is going to lead to disaster. The document I just mentioned assumes that we’re racing toward total disaster.

One thing that you’ve been criticized for, in the past, is not looking at people’s intentions, especially in the context of foreign policy. You say you don’t care so much about them. That’s where it seems like we were slipping up with the Stalin or Hitler comparison, where their intentions were obviously to get people killed.

I’m sorry. I don’t agree.

You don’t agree?

Stalin’s intentions were to maintain power and control. He didn’t purposely want to kill people. He had to kill people as a means toward this end. Take, say, Henry Kissinger. When he sends a directive to the American Air Force saying, about a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia, “anything that flies on anything that moves,” does he have the intention of committing genocide? Do I care? No. I just care that that’s what he said.

To return to a previous point: the left has often described Trump as a symptom of American decline or American bad behavior, and said that the real threat to American democracy is all of these things that have been true about us for a long time. The center-left has often described Trump as a uniquely malignant figure, who is threatening a democracy that was working better than some people on the left thought. You were seeming to come down on the latter side of that debate—which, given your status in the American left, I thought was interesting.

Sorry. I think [American] democracy, first of all, was never much to write home about. Do you really want to talk about it? The Founding Fathers, let’s go back to them. They were committed to reducing democracy. The major scholarly work on the Constitutional Convention, the gold standard for today, is Michael Klarman’s book, and it’s called “The Framers’ Coup”—their coup against democracy. The general population wanted more democracy. The Framers wanted to restrict that; they didn’t like the idea of democracy. Their picture was more or less that of John Jay: the people who own the country ought to rule it. James Madison explained that one of the prime goals of government is to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority, and the Constitution was designed to try to prevent what is called the tyranny of the majority, meaning democracy. You’ve got to protect the minority; the opulent have to be protected.

There are all sorts of ways in which this was done. There’s been a battle about that over the centuries. But since roughly 1980, since the neoliberal regression began, there has been a significant decline in the partially functioning democracy that existed before. That’s an immediate reflection of the policies that were chosen. You recall Reagan’s [first] Inaugural Address: government is the problem. What does that mean? Decisions are being made somewhere. If they’re not made in government, which is under at least partial influence of the population, they are being made in the private sector by unaccountable private institutions.

You take a look more closely, and 0.1 per cent of the population now hold twenty per cent of the wealth of the country. It’s had a major effect on the political system for perfectly obvious reasons. You have somebody elected to Congress. The first thing they have to do is get on the telephone, call the donors to make sure they’re going to be funded in the next electoral campaign. That’s the kind of democracy we had before Trump. He’s hit it with a wrecking ball and made it much worse.

Just to change tack for a minute, how old are you now?

Well, in a couple of months, I’ll be ninety-two.

What are your days like?

My days are mostly like this, except it’s usually Zoom rather than the telephone. Today, probably four hours of interviews; other days, talks. I gave a long talk Monday in Brazil, a couple of tens of thousands of people criticizing their government and its policies. The day before that, I gave a keynote address for the opening meeting of the Progressive International. It’s interspersed with interviews, talks, statements, meetings on technical scientific work that go on at the same time. So it’s pretty intense.

What do you do for fun?

I can’t say the word, or there’ll be a rush for the door by some canines at my foot, but that’s one of the things I do.

What are you most proud of in your career, and what do you most regret?

I can’t really answer that. One of the priorities I try to keep is to just keep away from personal questions. Things that are good, things that are bad—that’s for other people to judge.

I didn’t mean good or bad. Is there a book or talk or something you’re most proud of?

Well, when I look back, as I do often to look things up, I realize how much better [my earlier work] could have been. The kind of work I really like is the professional work. I mean, if the world would go away, I would be perfectly happy to just work on the problems of real intellectual interest. They are exciting. I think there’s been real insight into the fundamentals of language, mind, human thought, how it’s constructed, its nature, its origins, and so on. That’s really exciting work and much more engaging to the mind than what we’ve been talking about—which is very important but pretty much on the surface.

I interview a lot of people, and when I interview writers, they’ll often say, “Oh, too much time on politics. I wish I’d focussed on art or literature or science or something else, but politics has a way of taking up too much brain space and time.” Is that what you meant?

Time—but not much brain space. I mean to tell you the truth: while I’m giving interviews and talking about things, one part of my mind is working on technical problems, which are much more interesting.

So while we’re talking, part of your brain is focussed on language or science or something?

Yeah. Always. It’s just in the background, thinking about problems that have come up. What we’re talking about has to do with the most urgent things you can imagine—human survival, the fate of my grandchildren, all sorts of things. I’m reminded of a comment that Bertrand Russell once made, back around 1960 or so. He was asked why he was out marching at his age in anti-nuclear demonstrations, when he could be working on serious problems of philosophy for the ages. His answer was something like, if I’m not out here demonstrating against nuclear weapons, there won’t be anybody around to read the philosophy.

What about art? Are you a consumer of it?

Well, over the summers, I try to indulge myself by reading half a dozen novels or so, maybe going to a museum or going to concerts. This summer, I haven’t been able to do it. The tensions have been so high, the pace has been so intense, that I can’t even do things like that.

The tensions of what’s going on in the country, you mean?

And the world. For one thing, I’m absolutely bombarded with requests for talks and interviews. As I just said, the last couple of days, one in Brazil, one in Iceland, one somewhere else.

You could say no to some of them, right?

I say no to a large percentage of them, but they’re very important. This morning, I happened to have one with a small group in India. Some other time, it could be a group in southern Colombia. It’s all over the place. There’s a lot of people who really are doing very serious things. Interacting with them is extremely important for me—and I assume for them, because they keep asking. So, yes, all over. I must get probably a thousand letters a day. I try to answer what I can.

You’re famous for signing any petition sent to you.

Quite a lot of them. Nowhere near all, but a fair number. If I think they have any serious merit, like maybe saving somebody’s life. If I don’t like the way they’re framed, I won’t usually sign it.

I think the biggest controversy you ever had was probably the Faurisson affair. That fits into, I guess, what I said about you being willing to answer e-mails and letters and sign petitions or so on. Do you have any regrets about that and how that played out? [Four decades ago, Chomsky repeatedly defended the free-speech rights of Robert Faurisson, a French professor of literature and a Holocaust denier.]

No, I have no regrets about standing up for freedom of speech and opposing the Stalinist-style laws in France—which say that the state, the holy state, has the right to determine historical truth and to punish deviation from what it asserts. I have no reservations about opposing that.

You signed the Harper’s letter about free speech and “cancel culture.” What did you make of that letter?

That letter was so anodyne and insignificant; I barely noticed it. The only interesting thing about that letter is the reaction to it. The reaction was extraordinary. It showed that the problem is far greater than I thought it was.

Say more.

The problem was that people were outraged that somebody should make an anodyne statement, a simple statement, saying we should have some commitment to freedom of speech, even views we don’t like. I thought that’s the kind of thing people say to each other in their sleep. But apparently many people said, “No, can’t say that, too dangerous”—all kinds of crazed interpretations. Some of the interpretations were really wild. A lot of the protest was about the people who signed it. How can you sign a statement when such-and-such a person signs it? It takes thirty seconds of thought to understand that if you accept that principle, there are no statements, for very simple reasons. You’ve gotten plenty of statements to sign. Do you know who else is going to sign it? If the question of who else signs a statement is a criterion for signing it, then nobody in their right mind ever signs anything. Just that simple point of logic couldn’t fit the people who were so outraged that someone should say it’s not a good idea to shut people up.

Putting the Harper’s letter aside, I do think that people’s intentions matter and that we should take them into account. If a census worker says there are a lot of Jews working in Hollywood, stating it as a fact, that is different from Donald Trump saying it at a rally. We all know that one has different intent, and it seems like we should react to them differently based on the person saying it. Maybe this gets back to you not caring about intentions so much.

Yes, people read things differently. What I’m talking about is how they read it. Probably different signers had different intentions, no doubt. I can see that from the list of signers. But, as far as I was concerned, what’s in the back of my mind is very straightforward, and I’ve been saying it to activists for decades. Don’t pick up the techniques that are used regularly by the mainstream for repression. Don’t adopt them for yourself. So cancel culture didn’t happen to be mentioned in the statement, but a lot of people read that into it.

O.K., let’s say it’s talking about cancel culture. Cancel culture is all over the mainstream. I can give you plenty of examples from my own experience of things cancelled, books withdrawn, appearances on the national radio being cut off because somebody didn’t like it, some manager, some right-winger didn’t like it, endless numbers of this. It goes on all the time. That’s standard mainstream establishment behavior. People of the left are making a serious mistake when they try to imitate it. It’s wrong in principle; it’s wrong tactically. It’s a gift to the far right, and they run with it. They love it. In fact, Trump’s building his own campaign on it. Therefore, for the left, who I’m interested in, and their activists, pay attention to principle and tactical consequences. They are important. Pay attention to them and do not adopt the characteristic repressive behavior of the mainstream. That’s what I took the letter to mean.

I think one of the things people objected to was the letter saying that freedom of speech was becoming more and more constricted. To your point, this has always been going on, and has always been part of the mainstream, and some people thought that by saying it was getting worse, the drafters of the letter were making a specific point about the left and cancel culture.

Well, what you’re saying is correct. Worse, but that doesn’t mean it was good before. So to add a small fraction to what the mainstream always does is a mistake.

There’s also a lot more openness in certain ways. People of different races and gender identities are able to speak their voices more clearly now, and that in many ways—

That’s all to the good. That’s all positive and great. That’s what activism has been about. I’ve been part of it all my life and supported it, but it’s a mistake when you go beyond that to try to silence others.

Do you think that there’s any tension on the left between appeals for racial justice and gender equality and so on, and more class-based appeals?

It’s perfectly understandable that four hundred years of vicious and often extremely violent repression without end having left a bitter legacy—that that should be the highest concern for the United States. I’m talking about the fate of African-Americans, of course. It’s perfectly understandable that the marginalization, mistreatment, suppression of women’s rights should be a major concern. It’s also very significant to bear in mind that the United States has an unusually violent and brutal labor history and a long history of repression of labor. It’s gotten much worse since the neoliberals all began. Reagan and Thatcher, both of them, or whoever was behind them, recognized, right away, that if we’re going to hand everything over to the rich and the private sector, we’ve got to remove people’s ability to defend themselves, and the ability to defend themselves is primarily in the hands of labor unions. So the first moves they made were to impact and severely undermine the labor movement. That’s a brutal part of a long history. So, yes, that must be brought in as well.

Now, all of these things ought to be brought together. I’m sure you recall that Martin Luther King, Jr., at the end of his life, at the point where he was sharply losing liberal support, was trying to organize a poor-people’s campaign, Black and white, wherever you’re from—you’re poor, struggling, working people. That’s our campaign. That’s what ought to be done. All of these concerns interact. They’re integrated. They all ought to be dealt with. You can understand why, for some people, some of them are more important than others, but it’s a matter of bringing them all together, because they’re basically all on the same side. With regard to the huge crises that humans face, much worse than anything in their history, crises literally for the survival of humanity: on these, it’s not just a matter of black and white and others; it’s a matter of internationalism. These problems are all international in scale, and, going back to the Trump Administration, they’re smashing to pieces every part of international coöperation. It’s a major attack on the kinds of institutional structures that are going to be needed to overcome the enormous crises that are impending.

Το σκίτσο είναι του Βαγγέλη Παυλίδη

Το σκίτσο είναι του Βαγγέλη Παυλίδη

Στηρίξτε-Ενισχύστε την iΠόρτα με τη δική σας χορηγία…

Στηρίξτε-Ενισχύστε την iΠόρτα με τη δική σας χορηγία…